Public libraries tend to concentrate themselves in strategically-placed buildings so as to be effective at serving the majority of their populations. "Majority", however, does not mean "everyone", and for very rural people, or people who don't/can't cross various parts of their urban or rural space, public library service would be limited to any outreach the library does to their neighborhoods. Which can be nice, but is no substitute for being able to utilize all of the library's resources on a regular basis.

There's also the question of permanence for many objects. If I bought a paperback to read, and I have no intention of keeping it after I have finished reading it, what do I do with it? Donating it to the library will likely have it put into a book sale to raise money for the library, which means another person will pay a greatly reduced price for it and be able to enjoy the book (and possibly re-donate it when they are done, continuing to generate money for the library.). For some people, they want the books they are discarding to be read on a wider scale than one at a time, with a single price. For others, they want to have collections of materials freely available, but they can't trek to their library on a regular basis. And still others are trying to find ways of distributing their own materials on a wider scale without the benefit of a large publishing company behind them.

Little Free Libraries / PirateBoxen / LibraryBoxen

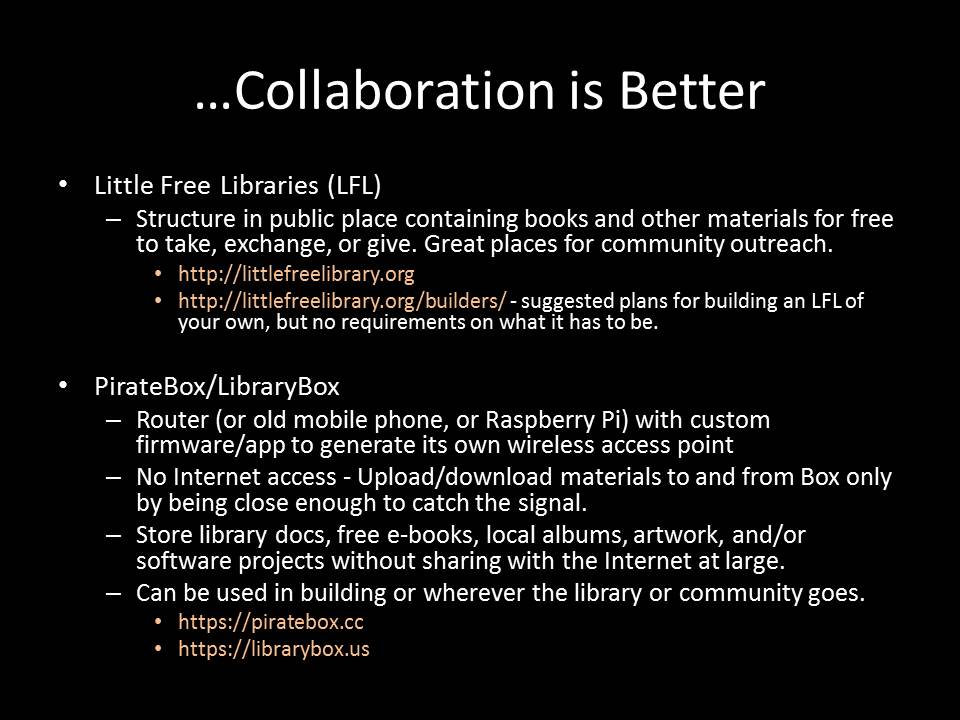

Enter Little Free Libraries. A Little Free Library (LFL) is a physical structure where the community surrounding it can exchange books, and possibly, other materials, and those materials will be protected from the elements and destructive abilities of the outdoors while they wait to be taken to a new home.

While you can purchase a ready-built Little Free Library for your area, there are also plans and guides available for people to build their own Little Free Libraries, with no set requirement on what a Little Free Library looks like. (Little Free Libraries would like a person that builds a LFL to register and pay a one-time fee to make it Official, though.) The Little Free Libraries are basically an open-source method for physical content exchange and distribution. Once built and placed, the community around can share their materials with each other. It's not a complete package of library services, but a public library with an outreach program might be persuadable to set up outreach stops near Little Free Libraries so as to provide a fuller library experience in those areas. If the Little Free Library is a busy one, it's already a guarantee that members of the community are going there. Your public library will hopefully understand that they don't have to search for a spot to reach your community if there's already one there to take advantage of. If not, explain it to them.

The Little Free Libraries concept covers physical materials (for the most part, anyway) that the community can exchange. What about digital materials? How cool would it be, in our increasingly gadget-filled world, to be able to offer a collection of hundreds of free e-books for our devices? Stop by the Little Free Library, exchange a few physical books, download hundreds more to your e-reader.

Jason Griffey has just the thing for you. Building on David Darts' idea for the PirateBox, an anonymous, peer-to-peer file-sharing, chat, and forum device restricted to the range of a wireless router running a customized build of OpenWRT, a rooted Android phone running the app, or other PirateBox setups for computers and routers, Griffey removed the ability for people connected to the device to upload content (because while public libraries are sharing institutions, they can only share as much as the law and any permissions granted allows them to) but otherwise kept the core of the PirateBox intact, and called it the LibraryBox. Since neither PirateBox nor LibraryBox requires an Internet connection, it's a perfect way of setting up content distribution in remote areas, areas with spotty connections, or anywhere else that someone would want to have a cache of electronic materials available for download without needing an Internet connection. LibraryBoxen also have the ability to synchronize themselves with a master box, so a public library that used a LibraryBox for distributing programming materials could easily update the available materials during an outreach stop, letting the master box change out the materials on the subordinate boxes.

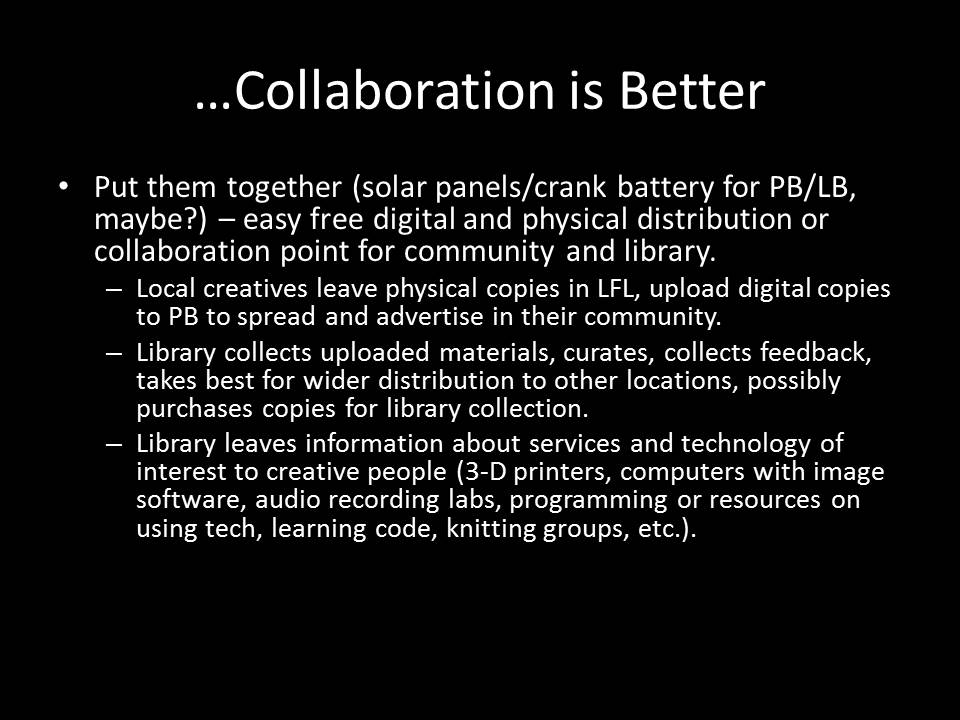

Putting these two ideas together would create something really cool. How awesome would it be if every Little Free Library in existence had someone add some photovoltaic cells, or a hand-cranked battery, or some other renewable, rechargeable power source that would power a LibraryBox so that in addition to the physical collection present, there were many more digital books available? Or program installation files and source code for open source projects? Or digital art from the community? All of those things would be possible with the LibraryBox attached. The result would be content distribution in even the most remote of places, for relatively inexpensive construction and operation costs, depending on your materials, using open-source ideas, plans, and possible community materials, to achieve that end.

Many public libraries have to be selective about their choices for the building shelves, because there's far more content produced, even by major publishing houses, than any public library could afford to purchase or has space to house. Public libraries rely on reviews from publications and award committee selections to winnow the field of possible purchases down to a manageable selection, where professionals at institutions apply their policies and expertise to choose what gets bought. Here's a secret: public libraries do like it when you tell them what you want them to buy – it gives weight to items in the sea, like positive professional reviews and awards do. The more you tell your public libraries what you'd like to see on the shelves, the more likely you're going to see what you like on the shelves. As a member of the public, anyway.

As an author, or content creator, it's a little harder to get yourself into the collection of the public library. Because of limited budget, the easiest way for a published author to get their books on the shelves is to have favorable reviews in major publications or win an award. If you don't have nice reviews or award stickers, convincing a lot of people around you that the public library wants your book is the next best thing. If you're fortunate, your public library may have a "local authors" or "local interest" shelf with slightly more relaxed rules about getting onto the shelf.

An accompanying PirateBox to a Little Free Library would allow the community to make suggestions about what they want to see on the LibraryBox, or to distribute resources of their own that can't or don't want the approval stamp of an institution like the public library. A public library could then curate the materials uploaded, select the things they want for wider distribution, and then put them back on the LibraryBox.

Little Free Libraries and LibraryBoxen are local solutions, primarly, meant for people who can physically journey to the locations to partake in what's available. If you want to distribute digital content on a wide basis, well, you're likely up the creek if you want your public library to help you out in getting to a wider audience – a lot of public libraries haven't given real thought about digital distribution methods that they can leverage to not only give a platform to their local audiences, but to archive and disseminate digital documents, free culture, and useful things, whether in the building or on the road, and to be able to access them from elsewhere.

How nice would it be to have space on a public library server for open source projects, both finished an in-progress? Where you could keep digital copies of documents, in addition to their print counterparts, should they exist, of organization meetings, government documents, and the rest? What if it could be combined with a search appliance to make the publically available document collections or projects indexed and searchable? Aspiring authors, would you be willing to let your library be the distribution hub where anyone can get your first novel, short chapters, preview work, or other important parts of your marketing plan, for free? Fan-creators, wouldn't it be neat if you could keep an accessible archive of your work at the library, in case of computer crashes or your preferred hosting service going under? Makers, would it be nice to have freely-available 3D printing designs, easily downloadable and manufacturable at the library? Local bands, why not sell your public library your album digitally, with the rights for the library to be able to check out the album to others, press CD copies of it, or just upload it to a space in the library's digital realm and let people expose themselves to it? What if your public library could help you with designing artwork or put you in contact with someone who would help design for you?

As an aspiring open-source institution, the public library is still going to do a lot of things with closed and proprietary methods because popular works and titles in demand are still locked into those methods, and the gatekeepers for those methods have marked interest in making sure the library gets good and properly gouged for the ability to loan out those books instead of forcing people to purchase them. Much like many people will use closed-source software because applications they need to use for their work or leisure only run on those closed-source platforms. But there's an entire ecosystem outside of those proprietary walls that has great stuff that should be in a public library collection. With items like the LibraryBox, public libraries can start building infrastructure to tap into that ecosystem. After building that infrastructure, though, the public library needs tools and community feedback to help find the really good stuff and promote it. Community feedback mechanisms and curation allow passionate people to help shape the amorphous blob of things into useful categorizations and bring the cream to the top. Public libraries already have the tools they need to begin this work. They don't know it completely, or they may encounter resistance from their organization, or they may not yet have processes and procedures in place to be able to sort the content that will flood in, but you can help them in all of those ways. Little Free Libraries and LibraryBoxen are two ways of addressing the need for the community to be able to distribute content. There may be better ones in this audience – make them! And share them with your public library and your community, so everyone can reduce their dependency on proprietary methods and materials.

Building A Community

In addition to building infrastructure for the sharing of things and tools, the public library needs to also be able to develop infrastructure so that they can help generate community and encourage the fostering of communities that see the public library as a valuable partner and resource. This is harder than it looks, but there are some success stories to emulate.

On-line: Teen Summer Challenge and Scout

In 2011, Pierce County Library System (PCLS) embarked on a radical re-thinking of the teen summer reading program. A program that was solely focused on books and accumulation of reading time for rewards wasn't reaching a whole lot of teens – the numbers were workable enough that the library system could hide behind this or that statistic to make it seem less of a failure, but a clear minority of people were the ones making up the majority of the recorded reading time. Rather than trying to promote books to teenagers (and there were always lots of good books to promote), the teen librarians at the time, Meredith Hale (@ladyluck131) and Jami Schwarzwalder, took the Search Institute's 40 Developmental Assets and paired them up with a new trend just emerging onto the World Wide Web - gamification. In gamification, activities that were normally just activities became wrapped in a game-like environment, adding points, badges, achievements, social elements, and more to produce a more game-like experience. As a guide, Meredith and Jami used Bartle's four types of MUD player, first released in 1996 (proving that librarians know how to make the old new again quite well), and given a more modern-looking form as the Bartle Test of Gamer Psychology to try and incorporate elements to the game that would appear to a diverse range of players.

Their conclusion was to discard the idea of reading (in its myriad forms) as the single defining thing for a summer program, and so reading became one of many activities and experiences laid out for teens in what is branded the Teen Summer Challenge. The challenge itself was spun out to a Wordpress installation, using mostly off-the-shelf plug-in components like BuddyPress to build the achievements, activities, leaderboards, and social spaces that would comprise the challenge, augmented where affordable through contact with the developers of those plugins and occasional commissioned code. The first year of the Challenge, 2012, did quite well in terms of participation (600+ registrations, of which a little over 50% performed an action to earn points) compared to the previous year's reading-only program (a little over 100 participants). Feedback was generally positive, and there was a lot of learning experience about building and running a community for the teen librarians and their supporting staff, dubbed the Grand Master Committee (GMC). (A fuller write-up of Teen Summer Challenge is available as a chapter in Teen Games Rule! A Librarian's Guide To Programs And Platforms) Since Teen Summer Challenge only officially runs during the school break in summer, if you want to observe the platform during a live session, you'll have to visit then.

The success of Teen Summer Challenge ensured a repeat performance in 2013 with better administration and tools in place to deal with the influx of material that had to be approved by the GMC to distribute points and badges. Initially, all activities for points and badges had to be approved by the The GMC. The committee understood, however, that increased participation would mean increased workload, and there would be a point in the process where it became unsustainable for the GMC to continue approving activities in its present form. Either more staff would have to be added to the GM group, or the platform and program would have to be re-worked again. The second year introduced the ability for players to "self-claim" the lower-level badges as a way of lightening the workload on the GMs. As a stopgap measure, this decision was effective, but the problem of scale still loomed large in the distance. Without some answer to that question, Teen Summer Challenge would continue to consume more staff time until it collapsed under its own weight.

To try and solve that problem and build on the success of Teen Summer Challenge by opening the idea up to a wider audience, PCLS secured a grant from the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation to build an "Interactive Discovery Platform" – an underlying framework, built around Wordpress, that multiple different programs could be run on top of to target different interests, age groups, and ability levels. The first two applications to come out of the IDP are a reworked Teen Summer Challenge, rebuilt to take advantage of the new platform, and Scout, which takes the concept first fostered and researched in the early incarnation of Teen Summer Challenge and throws it open for adults to take advantage of.

Regrettably, Pierce County Library System closed down Scout at the end of 02015. No word yet on whether the underlying code will be open-sourced so that others will be able to replicate the Platform for their own purposes.

The Platform, at the most basic level, offers activities that players can complete to collect an amount of points. Activities consist of self-claimable items ("I did it!"), items that request a response of some sort ("Write a paragraph about what you think / upload a picture of your completed efforts"), claim codes that are specific triggers (answers to questions, or specific phrases placed inside locations that are related to activities), referral links ("Ah, you've read to the end of our policies page. Click on this link here to get your points."), and, because we're a public library, people can input items with an ISBN to get points for activities like "Recommend a book for fans of television show X." Activities can be set to require a manual review of the submitted content by a moderator or administrators before approval.A group of activities all around the same theme forms a badge, which is awarded, along with optional bonus points, after the completion of all the activities in the group. Badges are organized into categories.

This doesn't make Scout, or Teen Summer Challenge for that matter, anything gigantically different than other gamification applications. I do think we're a bit different in that, once it's been robustly developed enough, we plan on releasing as much source code as possible so that everyone else can build their own applications on top of the platform, contributing back to the community that helped us build our platform.

What's most interesting about both Scout and Teen Summer Challenge is that they're building a community around the activities. Teen Summer Challenge's participants took to the social aspects of the platform faster, but both Teen Summer Challenge and Scout participants were soon mentioning each other, commenting on activities, and using their shared love of the subjects (and their sometimes personal knowledge of each other outside of the platform) as a focal point to interact with each other and the library staff in mostly positive ways. Staff, for their part, try to protect the community from spammers, trolls, cheaters, and other anti-community behaviors and encourage more interaction and detail from the submissions that come in. Staff are encouraged to organically suggest library or community activities that participants might find useful to continue their explorations or to help them get past a particularly difficult question. In Scout's Forums, some of the community members are also taking on those roles, with threads on how to do alternatives for activities where allergies will become a problem or for someone who doesn't have a readily-available camera and is supposed to take pictures. By trying to make the focus of Scout on the community, rather than on the activities, PCLS is hoping to build something longer-lasting and that will be used by more people.

The community aspect for Scout has also produced methods to collect feedback for the libraries to incorporate. An activity asks people to try out one of our downloadable services and tell us about how easy or hard it was to use. Another asks a player to go into one of our branches and ask for some book recommendations. From these activities, we find out useful things about the library that we may not have received through standard survey methods. We're happy to find that our staff gets consistently rated well by people on their knowledge and friendliness. And that one of our on-line partners is clearly being used head-and-shoulders above the rest for the challenge. The community gives us feedback; we adjust to meet the community's needs through our expertise and programs. That seems like the essence of a good open-source institution to me.

In Person: The 4th Floor

So, Little Free Libraries and LibraryBoxen are great at delivering content that's been selected by the community for inclusion. Programs like Scout and Teen Summer Challenge are trying to build a community of digital users to interact on library-curated and library-owned space, using and learning about library, community, and reputable Internet resources that are available to them. The last piece of this puzzle is transforming the physical library space itself to make it into a more open place where the community can use it and the resources available to advance their own interests, ideas, and even businesses. Most public libraries already open up their meeting room spaces to the community, and some public libraries are building dedicated spaces for various activities, like Makerspaces, fab labs, and media recording and editing labs. These are great starts toward a more open plan for library space and resources.

Chattanooga Public Library took things one step further. Instead of creating spaces designed for specific activities, they took the fourth floor of their library building and made it a wide-open lab for the public to come and do things with. The 4th Floor as it is now is an experimentation space, with several companies and startups working in partnership to hold events, use equipment, and provide the community with a big blank canvas that they can arrange to suit their needs. It's not just "here's a place where you can meet", it's "here's a place where you can launch your own business, with tools, knowledge, expertise, and events all available to help make that dream a success." Or "here's a place where you can pick up skills and use equipment that would be prohibitively expensive to acquire individually." Or "here's the place where you can drop an art installation, exhibit your work, and then pack it up and move on to the next spot, having exposed library people to something new and different." Common Libraries had a great write-up of the 4th Floor space and the uses the community in Chattanooga have found for it. By providing space for the community to remix, instead of just tools for the community to use in remixing their own spaces, Chattanooga opens up a possible way for the last component of an open-source institution – the way by which the community can make the walls, the floors, and the furniture suit the needs of the moment and of the long-term. How many other places in our lives can make the claim that the community shapes them as something other than the result of highly-focused demographic research meant to separate your money from your person?