And How

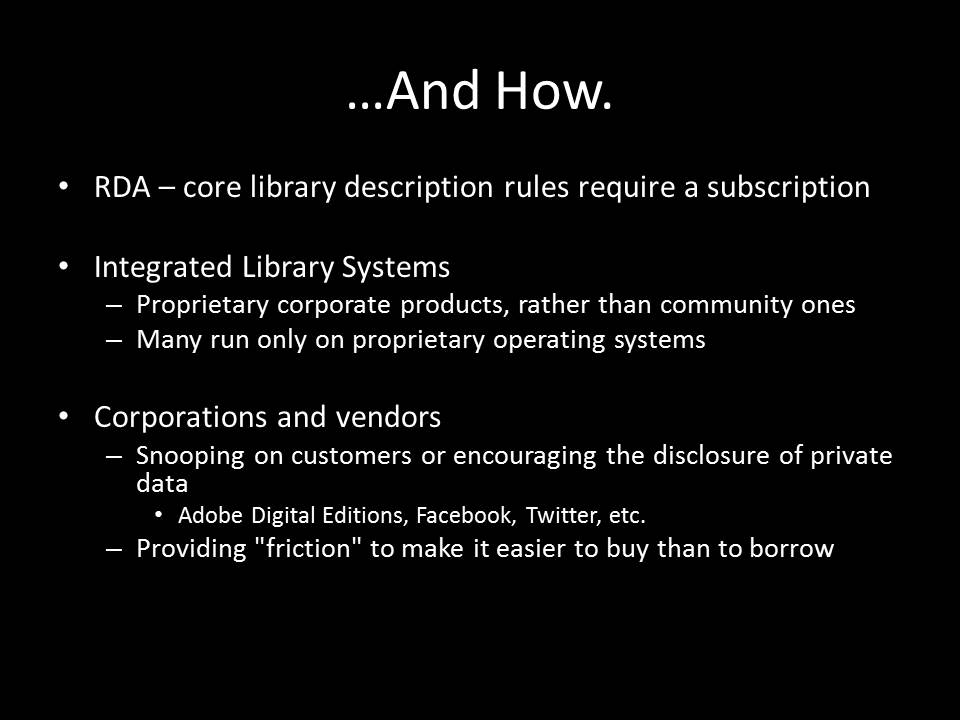

That failure extends in multiple directions, beyond one of the core functions of maintaining collections in public libraries ending up locked behind a paywall. Many of the ILS available run exclusively on proprietary operating systems like Windows, and are closed-source corporate products, as well. Users and libraries can request new features and hope that they're going to get them, but there's no way of unleashing a dedicated set of programmers on your ILS to get new functions into the source.

Furthermore, many of the products, services, and vendors that libraries contract with and that library users interact with on library computers engage in marketing to libraries and their customers, through advertisements, restrict the ability of library customers to use the product through non-optional DRM schemes, introduce "friction" or unnecessary steps in the process of borrowing a book from a library versus purchasing it from a vendor, or track their data and aggregate it into algorithms, sometimes overtly, often not. For example, a very popular program for reading lent library electronic books, Adobe Digital Editions (which contains an Adobe DRM scheme), started sending cleartext information about the reading habits of anyone that used the 4.0 release of the Adobe Digital Editions Software. The solution to the problem given to us by Adobe was not to openly cease with the spying, but Adobe reassured everyone that they were sending data that was encrypted instead of in the clear with the 4.01 release of Adobe Digital Editions. The underlying problem was not solved, only obfuscated.

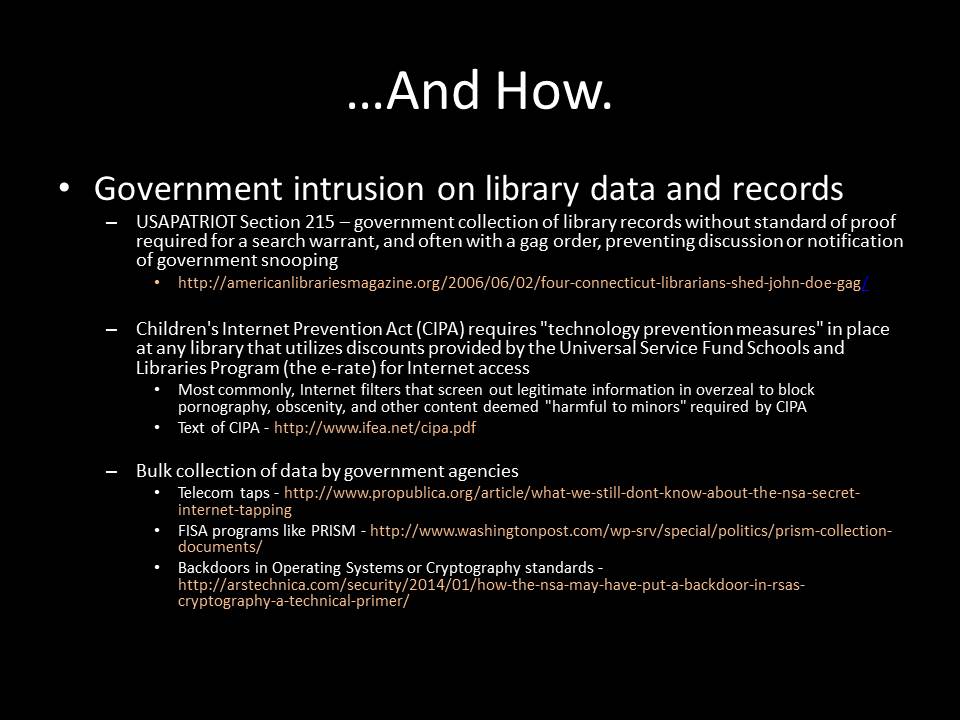

In addition to private enterprises, using laws like the Children's Internet Protection Act (CIPA), government intrudes and dictates to public libraries what they must do to prevent curious teenagers from reading accurate information about their bodies and their developing sexuality, in exchange for receiving a discounted rate on their Internet access. The requirement dictates a "technology prevention measure" to prevent minors from accessing content deemed harmful to them, which is most commonly implemented using filtering software, which is ineffective against a teenager with a modicum of curiosity and technical skill.

Using USAPATRIOT ("The Patriot Act") Section 215, the government can request any records kept by a public library. It does not require the standard of proof for the issuance of a search warrant to do so, and any library so served is often given a legal requirement to say nothing about the intrusion by the government into those records. The reason we know about the accompanying gag orders involved is because a library in Connecticut was able to successfully challenge the gag order in a Section 215 request in court after a protracted battle. Again, the underlying order was not countermanded, and so whatever was requested by the government still had to be delivered, but they could at least tell people that it happened.

Mentioning these laws is one way the government may be able to collect data that should be private. The government likely has the ability to directly capture information in one way or another, through the use of surveillance on communications systems, exploitation of flaws or deliberate backdoors installed or introduced into operating systems, or other methods that generally are not governed by open warrants or effectively overseen by the entities those agencies are nominally subordinate to. There's a lot still unknown about the breadth and depth of spying and surveillance programs, and there's no guarantee that legislators or anyone else with the power to effectively stop the programs knows the extent of the programs.

Public Libraries are screwed, right?

Even if we could fix many of the problems mentioned above through technical measures, there are underlying cultural issues involving public libraries and the perception of the public. Public libraries have often acted as gatekeepers of Approved Knowledge and Culture, and in a world where access to those resources was scarce and expensive, the public library was an excellent solution to the problem - it lifted the burden away from the individual and put it on the community. It would probably not be too far out of line to say that public libraries are now the victims of their own success using this paradigm.

If someone thinks about a public library as merely a repository of books or other physical materials to be browsed, checked out, and returned, then they deservedly have a rather dim view of libraries surviving into the digital age. Even if someone thinks of the library as a repository for all kinds of information, including digital collections, on-line journal access, and physical objects, they're still not liking our chances of survival. Who would blame them for thinking this? Google and other search engines improve daily by leaps and bounds in terms of finding any seemingly-random bit of data that's somewhere on the World Wide Web. What used to be a matter of ready reference tools (like almanacs) and specialized reference publications for finding data is now so well taken-over by search engines that they can predict what it is we're looking for before we even finish typing it.

What are you looking for?

- Movies?

- Netflix gives you an unlimited amount of discs and streaming offerings, limited only by how much you want (or can afford) to have out at any given time.

- TV?

- Hulu Plus, as well as streaming options through apps or websites for individual networks or channels, and even sport packages that allows for streaming of whatever games you fancy to whatever device can handle them.

- Books?

- There are a lot of players in that market, each of whom can give you a digital or physical copy of whatever you would like (so long as it's currently in print) as fast or slow as you would like, for a little bit of nothing.

- Music?

- The iTunes Store is doing brisk business in that regard, but there's also services like Bandcamp, as well as directly purchasing music from artist websites

- Video Games

- Valve's Steam is the leader here in streaming and DRM copies of games, with a slick interface, but there's also

Desura, Electronic Arts, GOG, Google Play, and the App Stores for Mac, iOS, Windows, and so on. - Physical objects?

- Amazon can get them to you in two days' or faster time (assuming you pay for that privilege).

And frankly, if none of those options appeal to you, there's always things like The Pirate Bay, one of the largest peer-driven content discovery systems in existence. Paired with the BitTorrent protocol, you have one of the fastest content-delivery systems in existence as well, assuming you are either properly anonymized or your ISP doesn't care about copyright violation fines and notices.

This should not be a new idea in public libraries. Eli Neiburger, a librarian (and many other things) at the Ann Arbor District Library, gave a talk in 2010 at a Library Journal / School Library Journal summit called Libraries At The Tipping Point called "Libraries Are Screwed". Both parts are available on YouTube - Part I talks about the large and looming threats that public libraries face in the new digital world, and Part II is about the ways in which public libraries can (have to) reinvent themselves to stay present and relevant to the new reality.

Public libraries have arrived at the point where people expect us to be as seamless as the other places and services they are used to. Unfortunately, in the digital realm, publishers and content providers tend to think of us as pirates, lending and sharing things that aren't really ours to people who haven't paid for them, rather than as valuable community partners. So they introduce "friction" into our processes to make it much more appealing for someone to buy a license for content with one click than to get it for free with libraries, which often involves two sign-ups, a login, and five more clicks. And that's assuming they let us into the market at all. Content providers and distributors have found ways to freeze libraries out of the process without having to contend with the rules that say "once you've bought something, you can do with it whatever you want to" by saying that public libraries are only licensing the content, instead of buying it, and so the public library has no real ownership or rights to do what they want with that content.

Public libraries cannot continue to exist merely as a repository for information and as a system for content delivery. There are far too many other entities and companies that can do that, and can do it better and faster than libraries can. Sure, you can't beat our price, but most people are willing to go with "I can get this quickly" over "I can get this for free". Commercial entities have a vastly more expansive collection of things to offer than our limited library budgets can dream of. We can't scale to that kind of degree to keep everybody happy.